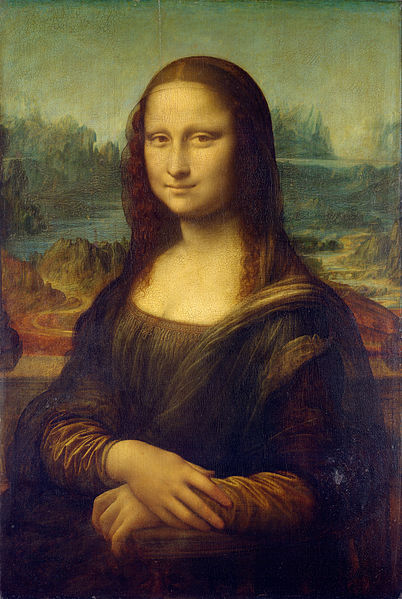

Leonardo’s Mona Lisa is one of the most famous paintings in the world. Today it is in the Louvre in Paris, but it was produced in Florence when Leonardo moved there to live from about 1500-1508. It is sometimes called La Jaconde in French (or in Italian, La Giaconda) because it is believed to be the portrait of the wife of Francesco del Giocondo, whose name was Lisa (Mona = short for “Madonna” (lady)). This identification was provided by Vasari in the sixteenth century, but this was later disputed. It is likely that the uncertainty over the sitter’s identification has added to the mystery and lure surrounding this painting over the years.

According to Vasari, the painting was not finished over the course of four years, which may have resulted in the difference in the craquelure (level of cracking on the surface) in the face and in the hands. The portrait shows what appears to be a typical portrait of a woman in which her wealth is not primary thing on display. She is veiled, her hands are crossed, and she has a faint smile – or some expression masquerading as a smile – which seems to capture the viewer’s gaze.

The way Leonardo painted this portrait deviated from the traditional way women were painted like this in Italy. Mona Lisa looks directly out at us, the viewers, which was something unconventional for a woman in a portrait to do at this time. She also appears rather content and assured in her demeanor, which reflected more the expectations of the aristocracy among men rather than among women. Further, until this point in time, portraits of both men and women were typically cut off in the middle of torso and hands were raised so that we the head and face and shoulders occupies more of the panel upon which the paint was applied. Here, however, the portrait shows not only the woman’s head and upper torso, but much of her body down to just below her waist. We see all of her arms, which are not raised up but resting comfortably on the armrests of her chair. The implication of this kind of view is that we are seeing the entire person, rather than just a sliver of her. Leonardo’s approach was innovative and would start a trend in portrait painting which would influence European painting into 1800s.

The way Leonardo has rendered the body of the woman is nothing less than extraordinary, and it truly reveals the jump forward in the level of naturalism that Italian painters made between 1400 and 1500. Leonardo makes use of his sfumato technique to show how the light bounces off her skin in certain places while leaving other parts in darker shadows. Her skin appears to be soft and smooth, and she looks quite like a real, though perhaps somewhat idealized, woman would look like right in front of us. Leonardo’s skill in this painting particularly impressed the sixteenth-century painter and historian Vasari, who had the following to say about it:

In this head, whoever wished to see how closely art could imitate nature, was able to comprehend it with ease; for in it were counterfeited all the minutenesses that with subtlety are able to be painted, seeing that the eyes had that lustre and watery sheen which are always seen in life, and around them were all those rosy and pearly tints, as well as the lashes, which cannot be represented without the greatest subtlety. The eyebrows, through his having shown the manner in which the hairs spring from the flesh, here more close and here more scanty, and curve according to the pores of the skin, could not be more natural. The nose, with its beautiful nostrils, rosy and tender, appeared to be alive. The mouth, with its opening, and with its ends united by the red of the lips to the flesh-tints of the face, seemed, in truth, to be not colours but flesh. In the pit of the throat, if one gazed upon it intently, could be seen the beating of the pulse. And, indeed, it may be said that it was painted in such a manner as to make every valiant craftsman, be he who he may, tremble and lose heart.

Apart from the naturalism in the figure, the painting includes a background which provides us with a stark contrast. Leonardo has placed Lisa against a vast landscape. The original loggia she was under was cropped out, but you can still see the base of the vertical supports to either side of her (at the right and left edges of the painting). If we look over her shoulder to the left side, we see a road that leads to distance, and mountains painted in a way which seems similar – at least on some level – to Chinese landscape painting of the preceding centuries. On the right side, we can see a bridge, and a road which leads to sea in the distance. It is in this vast landscape that we find a compelling juxtaposition in this painting. We have directly in front of us a touchable woman who is in the world of the here-and-now. She seems real to us – a very lifelike figure. Behind her we have a vast landscape which goes off into unknowable distances, and seems to continue on into a type of misty haze. The contrast between the woman and the background landscape is therefore quite remarkable, and it lends to the power of the painting.

Overall, the Mona Lisa is a masterpiece in portrait painting which has stood the test of time and continues to inspire and amaze visitors to the Louvre from around the world. Yet, if we consider it apart from its current role as a leading icon of pop culture in the modern world, we can very much see how this innovative work would have created an impression on Leonardo’s contemporaries in the sixteenth century. It is within this context of history that the Mona Lisa truly shines forth as a work of genius which caused Vasari to lavish so much praise.