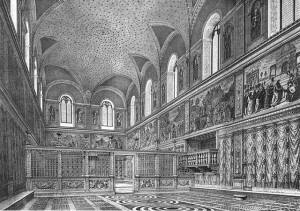

The Sistine Chapel is one of the most famous painted interior spaces in the world, and virtually all of this fame comes from the breathtaking painting of its ceiling from about 1508-1512. The chapel was built in 1479 under the direction of Pope Sixtus IV, who gave it his name (“Sistine” derives from “Sixtus”). The location of the building is very close to St. Peter’s Basilica and the Belvedere Courtyard in the Vatican. One of the functions of the space was to serve as the gathering place for cardinals of the Catholic Church to gather in order to elect a new pope. Even today, it is used for this purpose, including in the recent election of Pope Francis in March 2013.

Originally, the Sistine Chapel’s vaulted ceiling was painted blue and covered with golden stars. The walls were adorned with frescoes by different artists, such as Pietro Perugino, who painted Christ delivering the keys to St. Peter there in 1482.

In 1508, Pope Julius II (reigned 1503-1513) hired Michelangelo to paint the ceiling of the chapel, rather than leaving it appear as it had. Before this time, Michelangelo had gained fame through his work as a sculptor, working on such great works as the Pieta and David. He was not, however, highly esteemed for his work with the brush. According to Vasari, the reason why Julius gave such a lofty task to Michelangelo was because of the instigation of two artistic rivals of his, the painter Raphael and the architect Bramante. Vasari says that the two hoped that Michelangelo would fall flat, since he was less accustomed to painting than he was to sculpting, or alternatively he would grow so aggravated with the Julius that he would want to depart from Rome altogether.

Rather than falling on his face, however, Michelangelo rose to the task to create one of the masterpieces of Western art. The ceiling program, which was probably formulated with the help of a theologian from the Vatican, is centered around several scenes from the Old Testament beginning with the Creation of the World and ending at the story of Noah and the Flood. The paintings are oriented so that to view them right-side-up, the viewer must be facing the altar on the far side of the altar wall. The sequence begins with Creation, above the altar, and progresses toward the entrance-side of the chapel on the other side of the room.

Michelangelo began painting in 1508 and he continued until 1512. He started out by painting the Noah fresco (entrance side of chapel), but once he completed this scene he removed the scaffolding and took in what he had completed. Realizing that the figures were too small to serve their purpose on the ceiling, he decided to adopt larger figures in his subsequent frescoed scenes. Thus, as the paintings moved toward the altar side of the chapel, the figures are larger as well as more expressive of movement. Two of the most important scenes on the ceiling are his frescoes of the Creation of Adam and the Fall of Adam and Eve/Expulsion from the Garden.

In order to frame the central Old Testament scenes, Michelangelo painted a fictive architectural molding and supporting statues down the length of the chapel. These were painted in grisaille (greyish/monochromatic coloring), which gave them the appearance of concrete fixtures.

Beneath the fictive architecture are more key sets of figures painted as part of the ceiling program. These figures are located in the triangles above the arched windows, the the larger seated figures between the triangles. The first group include Old Testament people such as David, Josiah, and Jesse – all of whom were believed to be part of Christ’s human ancestry. They complemented the portraits of the popes that were painted further down on the walls, since the popes served as the Vicar of Christ. Thus, connections to Christ – both before and after – are embodied in these paintings which begin on the ceiling and continue to the walls.

The figures between the triangles include two different types of figures – Old Testament prophets and pagan sibyls. Humanists of the Renaissance would have been familiar with the role of sibyls in the ancient world, who foretold the coming of a savior. For Christians of the sixteenth century, this pagan prophesy was interpreted as being fulfilled in the arrival of Christ on earth. Both prophets from the Old Testament and classical culture therefore prophesied the same coming Messiah and are depicted here. One of these sibyls, the Libyan Sibyl, is particularly notable for her sculpturesque form. She sits on a garment placed atop a seat and twists her body to close the book. Her weight is placed on her toes and she looks over her shoulder to below her, toward the direction of the altar in the chapel. Michelangelo has made the sibyl respond to the environment in which she was placed.

It has been said that when Michelangelo painted, he was essentially painting sculpture on his surfaces. This is clearly the case in the Sistine Chapel ceiling, where he painted monumental figures that embody both strength and beauty.

should be noted that after the death of Michelangelo, the painter Daniele da Volterra was commissioned to cover some nudity in the frescoes.

Few of these changes were elimininate during the restoration completed in 1994.