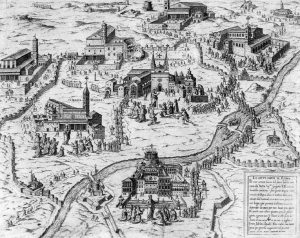

Rome is a city like no other, though its status by the time of the fourteenth century was only a shell of its ancient self. The population of early imperial Rome likely reached one million inhabitants, though perhaps it was as high as two million. However, in the late years of the empire, its population was in decline; its population went from approximately 800,000 in the fourth century to about 500,000 in the early fifth century, before entering an even more dramatic phase of population decline to about 80,000 by 530. Meanwhile, the inhabitants started moving away from the hills and outskirts of the city and toward the area where the Tiber River makes its curve. An incredibly sullen transformation to the the capital of a once-great empire. Welcome to medieval Rome.

Yet just as the city declined, a new force was simmering within its walls. Christianity was beginning to spread through Europe during the first several centuries AD, and Rome was the seat of the bishop of Rome, otherwise known as the pope. Rome also retained an important distinction among European cities because it was here that so many of the early Christian witnesses to their faith were martyred at the hands of pagan officials. Christians began to visit the tombs where these martyrs were buried outside the walls of Rome, and martyrium churches were built to protect the veneration of these relics. These visitors started to come to Rome from all over Europe in the Middle Ages, helping to elevate Christian pilgrimage to the level of a major industry throughout the medieval period.

Pilgrimage continued to be a major economic driver for Rome into the Renaissance period, particularly during the Jubilee Years, which were designated as penitential events when pilgrims were given the opportunity to obtain plenary indulgences. Although first initiated in 1300 by Pope Boniface VIII, it was not until 1450, when there was a pope actually residing in Rome, that the Jubilee Year became a major event. In that year, the crowds became so significant that armed militia was called in to maintain order. The masses of pilgrims that year brought a dramatic increase in offerings, so much that Nicholas V made a bank deposit of some 100,000 gold florins, an increase of 1/3 over deposits made in normal years.

By means of these Jubilee pilgrimages, Rome became the leading destination site for pilgrims in much of the West. The printed word aided in drawing many of them in, as dozens of editions were published of the popular pilgrim guidebook, Indulgentiae ecclesiarum urbis, in the late-15th and early-sixteenth centuries. The effects of having a large number of pilgrims stream into Rome included the elevation of the papacy’s spiritual authority and an increase in the income of the popes. Despite the past successes in bringing pilgrims to the city, the Jubilee Years of the Renaissance did not always fare well. The year 1525 was one such Jubilee when the onset of Lutheranism, recent plague, the Colonna rebellion, a foreign military presence in a nearby region, and impending the Sack of Rome (and aftermath) in 1527 made travel during this decade extremely difficult. This setback was only temporary, and may have forced future popes to become more proactive in facilitating pilgrim visits to the city.

One of the popes who took a proactive role in enhancing the experience of pilgrims in Rome was Sixtus V, who initiated an intensive remodeling campaign of the city streets that made the flow of pilgrims between the old Christian churches more efficient. When many of these churches were built in late antiquity, they were located on the periphery of the ancient city and after the Middle Ages it became difficult for the visitors entering through the Porta del Popolo to easily navigate to these sites. Sixtus had his architect Domenico Fontana create several new avenues through the dilapidated sections of Rome so that churches like Santa Maria Maggiore, Santa Croce, and San Lorenzo were linked by streets. Connecting the major churches and shrines in Rome by roads not only benefited pilgrims, but it also reflected the papacy’s desire to show the city’s resilience during the Counter Reformation. In doing so, Sixtus aimed to make the entire city a shrine.

Further reading

Rome in Late Antiquity: Everyday Life and Urban Change, AD 312-609, by Bertrand Lancon