Donatello had been working in Florence for many years before he eventually moved to northern Italy and to the city of Padua, which was under Venetian control at the time. He worked for over ten years there, during which time he gained a following and would go on to have a significant influence on painting and sculpture in the region.

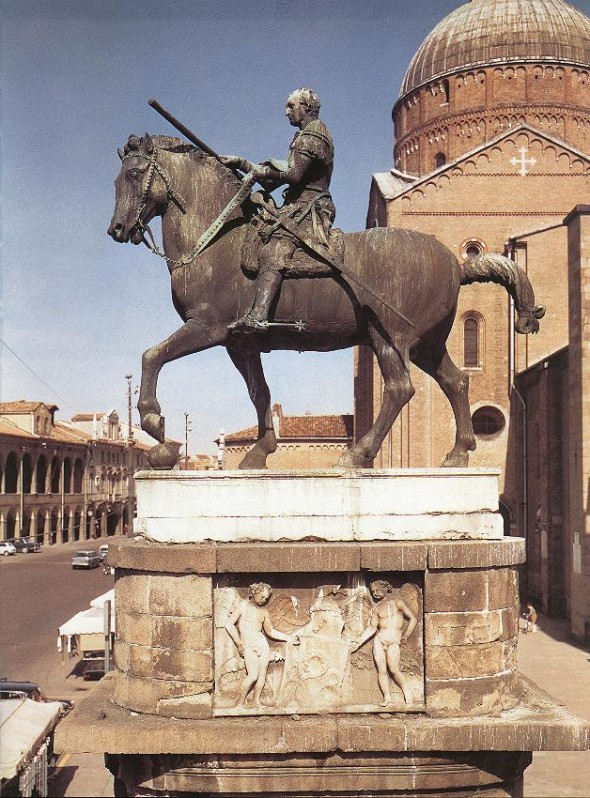

One of the great works Donatello created while in Padua was the Gattamelata, the name of which means “honeyed cat”. This funny-sounding name was the nickname of Erasmo da Narni, a condottiere (mercenary) who fought for Venice and is the person depicted riding the horse. Normally, equestrian statues could legally only depict rulers, which Erasmo was not. It is therefore likely that the Venetian Senate had to authorize the creation of this work by making an exception to its rule.

The city of Padua wanted to honor Erasmo after his death, and they did so by placing this equestrian statue of him in front of the main church in the city. While equestrian statues of this type may not seem notable to us nowadays, in the mid-fifteenth century, it was significant at the time for its naturalism and the way it rivaled ancient sculpture. While there had been some other equestrian works executed over the centuries, there were none like this. According to Vasari, the work was compared to antique sculpture during the Renaissance. He wrote that Donatello “proved himself such a master in the proportions and excellence of so great a casting, that he can truly bear comparison with any ancient craftsman in movement, design, art, proportion, and diligence wherefore it not only astonished all who saw it then, but continues to astonish every person who sees it at the present day.”

The city of Padua wanted to honor Erasmo after his death, and they did so by placing this equestrian statue of him in front of the main church in the city. While equestrian statues of this type may not seem notable to us nowadays, in the mid-fifteenth century, it was significant at the time for its naturalism and the way it rivaled ancient sculpture. While there had been some other equestrian works executed over the centuries, there were none like this. According to Vasari, the work was compared to antique sculpture during the Renaissance. He wrote that Donatello “proved himself such a master in the proportions and excellence of so great a casting, that he can truly bear comparison with any ancient craftsman in movement, design, art, proportion, and diligence wherefore it not only astonished all who saw it then, but continues to astonish every person who sees it at the present day.”

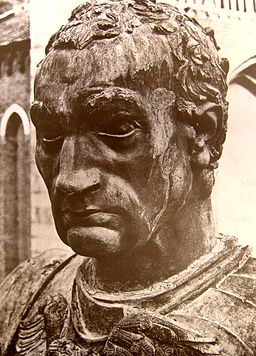

The statue is situated on an elliptical base, and Erasmo is dressed in military gear – he is wearing armor and has his sword by his side. His body is in natural proportion to his horse (something that is not always true with other equestrian statues), which indicates that Donatello was trying to achieve a high level of naturalism here. Erasmo is not shown as a deity, but instead as someone who conveys intelligence, courage, and confident – a rather triumphant figure who rides on a horse with its hoof on an orb, a symbol of power.

Overall, this is a work that is reminiscent of a famous antique equestrian statue depicting the emperor Marcus Aurelius. However, whereas that statue honored an all-powerful figure, this figure honors someone who did not rule, but only worked on behalf of a civic authority. Donatello (and those who commissioned the work) looked to antiquity to revive this form of monumental sculpture, but the glorification of someone of lesser rank seems to be more in keeping with contemporary humanist practices of honoring individual achievement.Donatello received praise for his work done in Padua, but rather than making him want to stay there, it had the opposite effect on him and made him want to leave. Vasari says that he “determined to return to Florence, saying that if he remained any longer in Padua he would forget everything that he knew, being so greatly praised there by all, and that he was glad to return to his own country, where he would gain nothing but censure, since such censure would urge him to study and would enable him to attain to greater glory.” For Donatello, motivation to achieve greatness came about more through criticism than through praise.