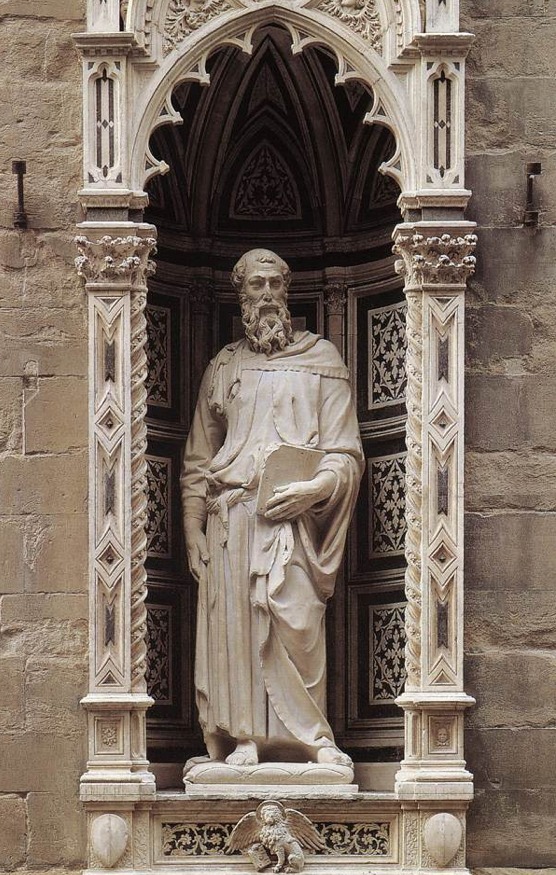

The statue of St. Mark was commissioned by the linen guild, one of the poorer guilds in Florence whose patron was St. Mark. They decided to hire the sculptor Donatello for the commission, who created a larger than life-size work (it is 7’9” tall). The work itself was placed into a niche that was already in existence in the building called Orsanmichele, and probably because this meant only the front would be visible, the back side of the statue was not completely carved.

The result of Donatello’s work was profound, to say the least, as he revived the use of the contrapposto stance in freestanding sculpture. Contrapposto had been employed by many ancient Greek and Roman sculptors, dating back to the Classical period of Greek art beginning around 480 B.C. After the fall of the Roman empire, however, it was largely forgotten by Europeans in the Middle Ages. When medieval sculptors depicted the human figure in reliefs (and less frequently, in free-standing works), the figures would often times be given stylized body parts and rigid postures. Donatello starts to change this in large-scale freestanding sculpture by giving St. Mark a much more natural look through the use of contrapposto. He would have known about this sculptural device through the trip to Rome that he probably took with Brunelleschi early on in his career. In Rome, the remains of reliefs and freestanding works would most certainly have been more prevalent than in any other part of Italy (or Europe for that matter), giving artists an opportunity to study them first-hand.

In addition to the use of contrapposto, another ingenious aspect of the St. Mark is the way Donatello anticipated the way the statue would be seen from below. The niche in Orsanmichele in which the work was originally placed was along the street, a bit above eye-level. Donatello made St. Mark’s head and hands and torso over-sized or elongated a bit so that they compensated for the angle that people viewed this from. Donatello was thus taking the viewing angles of the statue into account in his approach, and this is something that other artists would pick up on in the Renaissance.

Because the guild for which St. Mark was made was the linen guild, Donatello emphasized the garments on the figure. Here, the cloth covering his body falls over him like it would fall over an actual body with clothing on it. This way of modeling a body with garments is quite different from the way it had been done at times during the Middle Ages, when artists would depict a body hidden inside a mass of garments. Here, we can see how St. Mark’s right leg carries the weight and is made column-like for emphasis, but his left knee and leg are clearly detectable under his robe. Meanwhile, as his left hand holds the Gospel book, his right hand grasps at his side as if he is receiving divine inspiration to write the Gospel. He stands atop a pillow, which is typically a symbol of holiness; here, however, it also puts some emphasis on his weight and conveys to us the idea that he is a real person because the physical world around him reacts to his body.

Because the guild for which St. Mark was made was the linen guild, Donatello emphasized the garments on the figure. Here, the cloth covering his body falls over him like it would fall over an actual body with clothing on it. This way of modeling a body with garments is quite different from the way it had been done at times during the Middle Ages, when artists would depict a body hidden inside a mass of garments. Here, we can see how St. Mark’s right leg carries the weight and is made column-like for emphasis, but his left knee and leg are clearly detectable under his robe. Meanwhile, as his left hand holds the Gospel book, his right hand grasps at his side as if he is receiving divine inspiration to write the Gospel. He stands atop a pillow, which is typically a symbol of holiness; here, however, it also puts some emphasis on his weight and conveys to us the idea that he is a real person because the physical world around him reacts to his body.

This is the first time in the Renaissance that a statue like this is made where garments echo the body’s form like this. It signals a break from the International Gothic style that preceded it, and helps to usher in a new era of increasingly natural figures carved and cast in life size or larger.