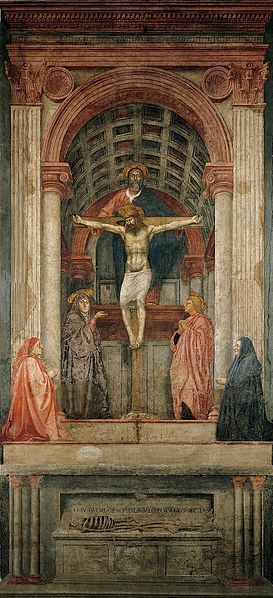

In the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence is one of the best examples of the early Renaissance scientific approach to creating the convincing illusion of space within a painting. It is here, on one of the walls inside the church, that Masaccio painted his fresco of the Holy Trinity in 1424. The title of the painting comes from the three key figures: Christ on the cross, God the Father standing on a ledge behind Christ, and the Holy Spirit. Interestingly, God the Father is shown standing on a platform in the back, which is not an “otherworldly” place (where he would be traditionally depicted), but instead a realistic space which follows the laws of physics. Mary and St. John are also present at the Crucifixion at the foot of the cross, and one step down from them are Masaccio’s donors to either side. Unlike the biblical and divine figures, the donors are meant to appear to be in our space (the space of the viewer), and not in the recessed space in which the cross is located.

If we look at the composition of the figures, we see that they are in a kind of pyramidal  shape. This is similar to composition of many other Renaissance works, such as Brunelleschi’s competition panel for the bronze doors of the Florence baptistery.

shape. This is similar to composition of many other Renaissance works, such as Brunelleschi’s competition panel for the bronze doors of the Florence baptistery.

The architecture in which the Crucifixion takes place is also significant. We see what looks like a Roman triumphal arch, with a coffered ceiling, barrel vault, pilasters, and columns. This type of structure hearkens back to Roman architecture, and indicates the type of interest that Masaccio (and others at this time) had in antique buildings.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of this fresco is the way Masaccio makes use of one-point linear perspective to convey the sense that the images recedes back in space. The coffers on the ceiling create the orthogonal lines, and the vanishing point is at base of cross, which happens to be at the eye level of the viewer. This creates the sense that the space we are looking at in the fresco is actually a continuation of the chapel space in which the fresco is painted. Masaccio paid extremely close attention to the dimensions of the objects and spaces that he painted, so much so that you can actually determine the dimensions of the room we are looking at in the fresco.

Moving our eyes down the fresco, we see a skeleton in a tomb at the bottom. This part of the fresco had been covered over for many years, and it was not until recently that it was uncovered. The tomb is meant to appear as an outward projection, but it also has its own recess near the area where the skeleton lay. Above the skeleton is an inscription, which states (translated), “What you are I once was; what I am, you will be”. This message tells us of our own (the viewer’s) mortality and future death. In the end, we will end up like the skeleton as well. This morbid message projects out into the viewer’s space, but when we look above we see a message of hope in the Crucifixion, which means freedom from death for believers. Note how the vanishing point, at a level between the tomb below and the cross above, unites the two different spaces. Masaccio approached this fresco in a very rational way to masterfully create a convincing illusion of space, and he has done so in a way which elevates the important Christian meaning at the core of the scene.

Moving our eyes down the fresco, we see a skeleton in a tomb at the bottom. This part of the fresco had been covered over for many years, and it was not until recently that it was uncovered. The tomb is meant to appear as an outward projection, but it also has its own recess near the area where the skeleton lay. Above the skeleton is an inscription, which states (translated), “What you are I once was; what I am, you will be”. This message tells us of our own (the viewer’s) mortality and future death. In the end, we will end up like the skeleton as well. This morbid message projects out into the viewer’s space, but when we look above we see a message of hope in the Crucifixion, which means freedom from death for believers. Note how the vanishing point, at a level between the tomb below and the cross above, unites the two different spaces. Masaccio approached this fresco in a very rational way to masterfully create a convincing illusion of space, and he has done so in a way which elevates the important Christian meaning at the core of the scene.

Paintings of Masaccio were rediscovered in the last 50 years. The triptych of St. Juvenal, the painting Madonna Casini etc.

As it was some time for the frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, some work was in collaboration with Masolino.